Mastering Scale Insect Identification: A Complete Guide

Written by

Liu Xiaohui

Reviewed by

Prof. Martin Thorne, Ph.D.Become proficient in scale insect identification by learning to differentiate armored from soft scale cover types.

Place tape on plant surfaces to detect crawlers when they are transitory nymphs that can be treated.

Know the species by its unique shape i.e. circular shells or cottony domes.

Recognize honeydew residue and sooty mold as evidence of soft scale infestation.

Dispel the myths that only soft scales produce honeydew and armored scales inject toxins.

Take unknown specimens to your local agricultural extensions for identification by a specialist.

Article Navigation

To understand the intent of scale insect identification, it is essential to recognize that they are part of the Hemiptera and comprise hundreds of thousands of species worldwide. I have witnessed gardens destroyed overnight, all due to the owners overlooking the early signs of neglect. Accurate identification can prevent severe damage to a plant from escalating to the permanent death of a tree.

You will run into two overall types: armored scales with their hard shell that can be pulled off or soft scales that produce a sticky substance called honeydew. Honeydew develops black fungus, or sooty mold, at its surface. Noticing whether scales are armored or soft tells you quickly what enemy you are looking at in your garden.

Armored vs. Soft Scales

The most crucial first step in scale insect identification is the differentiation between armored and soft scales. Armored scales will develop hard detachable covers that you can flick right off to find a tiny insect below. Soft scales will feature waxy attached covers that blend with the surfaces of the plant. The type of scale dictates the approach for control.

You will recognize honeydew production as a telltale sign of soft scale infestation. Only soft scales leave behind this sticky sugary substance! It coats plant leaves and attracts ants, while feeding the sooty mold fungi. That black coating blocks sunlight and chokes plants. The armored scales never create this sticky mess.

Size categories assist with identification. Armored scales and armored insects are from 1/16 to 1/8 inch in size, which is from 1.6 to 3.2 mm in size. They appear like tiny oyster shells. Soft scales are 1/8 to 1/2 inch (3.2 to 12.7 mm) in size and appear as bumps on stems. The maximum size for scales is the magnolia scales.

The damage patterns reveal information that can help identify the types of scales. Armored scales inject toxins into twigs that create yellow halos (rings) around the feeding sites. Soft scales suck sap out of twigs, excreting honeydew that weakens them. Both types kill twigs and plants, but do so using unique biological mechanisms. Therefore, they require different types of interventions.

Oystershell Scale (Armored)

- Appearance: Elongated brown cover resembling oyster shell, 1/8 inch (3.2 mm) long

- Location: Bark of ash, dogwood, lilac, and maple trees

- Damage: Causes yellow halos on leaves and branch dieback

- Unique Feature: Two generations per year with crawlers active in spring

- Control Tip: Apply dormant oil in early spring before leaves appear

San Jose Scale (Armored)

- Appearance: Circular black cover with gray concentric rings, 1/16 inch (1.6 mm) diameter

- Location: Fruit trees, shade trees, and ornamental shrubs

- Damage: Kills plant cells around feeding sites causing leaf drop

- Unique Feature: Up to three generations per year globally

- Control Tip: Target crawlers in June, July, and September

Magnolia Scale (Soft)

- Appearance: Largest US scale at 1/2 inch (12.7 mm), brown-purple with white wax

- Location: Twigs of magnolia trees resembling plant buds

- Damage: Heavy honeydew production coating leaves and branches

- Unique Feature: Crawlers born alive in fall rather than hatched from eggs

- Control Tip: Use systemic insecticides during crawler activity

Brown Soft Scale (Soft)

- Appearance: Oval, flat, yellowish-brown with dark grid-like mottling, 1/8 inch (3.2 mm) long

- Location: Undersides of leaves on gardenia, fern, and fig plants

- Damage: Copious honeydew attracts ants and promotes sooty mold

- Unique Feature: Common on houseplants with continuous reproduction indoors

- Control Tip: Wipe leaves with soapy water and apply horticultural oil

Cottony Maple Scale (Soft)

- Appearance: White cottony egg sacs on twigs up to 1/4 inch (6.4 mm) long

- Location: Maples, boxelders, and other hardwood shade trees

- Damage: Sooty mold coats leaves reducing photosynthesis

- Unique Feature: Crawlers migrate from leaves to twigs in fall

- Control Tip: Treat in early June when crawlers are active

Life Cycle & Identification Features

Understanding scale life cycles will change the way you recognize the signs of scale. Under their protective covering, eggs will hatch in 1-3 weeks, and you will see... mobile crawlers. While they remain tiny and legged, they are mobile nymphs, and they will be searching for feeding sites. This stage will only be mobile before it settles permanently.

Crawlers progress through three instar phases, losing mobility progressively, with females producing waxy covers and males developing wings for a short period. Adults basically become immobile eating stations. This immobility operates under the rationale for the clustering behavior of scales on plants in colonies.

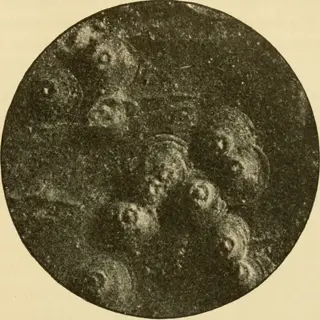

Markers facilitate the identification of spots such as circular shells or cottony domes. Length should be accurately measured using metric conversions where 1mm equals 1.0 m. The tiny armored scale can reach a maximum length of 1.6 mm, while the large soft scale can be up to 12.7 mm in length. The shape and relative size are identifiers of species more quickly than color differences.

Always keep in mind that honeydew residue is an indication of soft scale only. The sticky coating attracts sooty mold, creating leaves with black coloration. Again, armored scales will not produce honeydew. Damage from armor scales will appear as yellow halos around their feeding sites, displaying damage caused by toxins.

Egg Stage

- Duration: 1-3 weeks under female's protective scale covering

- Appearance: Tiny, oval-shaped eggs often visible only under magnification

- Location: Protected beneath adult female's body on plant surfaces

- Vulnerability: Most susceptible to horticultural oils before hatching

Crawler Stage

- Duration: Mobile for 2-7 days before settling to feed

- Appearance: Pinhead-sized (0.5mm), pale nymphs with functional legs

- Behavior: Wind-dispersed; search for feeding sites on leaves/stems

- Control Window: Most effective treatment timing with insecticidal soaps

Instar Development

- Duration: 2-8 weeks with 3 molting phases depending on species

- Physical Changes: Gradual wax cover formation; leg/antenna reduction

- Feeding Impact: Sap extraction intensifies causing leaf yellowing

- Gender Differentiation: Males develop wings; females lose mobility

Adult Stage

- Lifespan: 2-6 months while reproducing

- Mobility: Females immobile under waxy covers; males short-lived flyers

- Reproduction: Females lay 50-2,000 eggs or live young (species-dependent)

- Identification Peak: Distinct cover shapes/colors fully developed

Overwintering Behavior

- Timing: Occurs during colder months when plants are dormant

- Form: Most species overwinter as eggs or immature fertilized females

- Protection: Scales develop thicker waxy coatings for insulation

- Location: Sheltered spots on bark crevices or leaf undersides

- Control Strategy: Dormant oil applications smother overwintering scales

5 Common Myths

Scale insects are not actually insects, but are some type of plant fungus or growth.

Scale insects belong to the order Hemiptera, which makes them true insects consisting of over 8,000 described species. They undergo complete metamorphosis, with four stages in their lifecycle - egg, crawler, nymph, and adult. What can make scale insects look strange is the waxy coverings that they secrete for protection, not the growth of fungus. Like all insects, they have a number of legs, six in total, and a reproductive system that handles sex in very unusual ways when living as crawlers and emerging from eggs.

All scales secrete a sticky honeydew that results in sooty mold issues

Only soft scales (Coccidae) are able to convert their sugary food to honeydew (due to their sap-feeding style). The armored scales (Diaspididae) do not have the ability to secrete this appetizing sugar. The honeydew from soft scales feeds sooty molds fungi that blacken leaves, while the armored scales only cause damage by injecting toxins into the plant, and do not deposit any sticky honeydew.

Scale insects can move or fly to a new plant for their whole live

The only time mobility is present is with the crawler stage (first instar nymphs), which have legs and can move short distances. Once settling, female scales are immobile for their entire life and lose their legs and antennae. Adult male scale insects in some species develop short-lived wings; they complete their mating period and die quickly without feeding.

Chemical pesticides effectively kill adult scales although they develop a waxy covering

The waxy covers of adult scales are very resistant to most pesticides. Effective control is most achievable while the scales are crawlers before they have acquired action to develop a protective coating and waxy covering. Horticultural oils will function as suffocation when the scales are dormant. Systemic insecticides are partially useful, even though they are limited in penetrating the wax barriers of adult scales.

Scale insects primarily infest weak or dying plants that are already in bad health.

Scales infest healthy and stressed plants in equal proportions and that scales infest only specific host species regardless of plant vigor. Outbreaks happen as a result of environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and lack of natural predators, not as a result of the plant's health. In fact, some scale species actually prefer actively growing new foliage on otherwise healthy plants.

Conclusion

Successfully identifying scale insects is a matter of remembering a few key differences. The armored scales have removable hard coverings and inject toxins into their host plants, giving plants distinctive yellow leaf halos. Soft scales are covered in wax that is attached to their bodies and produce sticky honeydew that attracts sooty mold. These simple distinctions will affect how you proceed with your control measure.

During the crawler season, you should implement a proactive monitoring technique using tape tests. Use clear tape to wrap around branches that you suspect have been infested. By doing this, you will get a sample of the mobile nymphs. I have successfully prevented outbreaks by catching crawlers in this manner. It is a simple method that highlights, in an obvious manner, different stages of infestation that require immediate treatment.

Give priority to *biological controls*, such as lady beetles and parasitic wasps. These beneficial insects reduce scale populations without the use of insecticides. Release predators early in the season when crawlers appear. Biological controls have saved my citrus trees after they were damaged by the cottony cushion scale.

You can take your unknown specimen to your local extension service for an expert identification of the specimen. Most county agricultural offices do not charge for the analysis. I regularly send samples in a sealed bag along with information about the plant. Timely and accurate identification will prevent misidentification and ensure proper treatment of the plant.

External Sources

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I distinguish scale insects from similar pests?

Scale insects are often confused with mealybugs or plant buds. Unlike mealybugs' fluffy wax, scales have smooth, shell-like covers. True scales remain stationary once settled, while aphids and thrips move freely. Magnolia scales mimic buds but secrete sticky honeydew.

What's the most effective way to eliminate scale infestations?

Target crawlers with insecticidal soap during their mobile stage. For adults, use horticultural oil to suffocate them. Prune heavily infested branches and physically remove scales with alcohol-dipped swabs. Introduce natural predators like lady beetles for long-term control.

How do I identify scale insects on indoor plants?

Look for brown soft scales on fern leaves or hemispherical scales on schefflera. Check leaf undersides for dome-shaped bumps and sticky honeydew residue. Use a magnifier to spot tiny crawlers or waxy covers resembling miniature tortoise shells.

Can scale insects disappear without treatment?

Scale populations rarely vanish naturally. Without intervention, they multiply rapidly, causing leaf drop and plant death. Natural predators like parasitic wasps may suppress them, but proactive control is essential to prevent irreversible damage.

What spray works best against scale insects?

Insecticidal soap effectively kills crawlers, while dormant oil smothers overwintering scales. Systemic insecticides offer partial control but struggle against waxy adult covers. Always apply treatments during crawler activity for maximum penetration.

Does vinegar eliminate scale insects?

Vinegar lacks scientific backing for scale control. Its acidity may damage plant tissues without penetrating waxy covers. Proven methods include horticultural oils and soaps that disrupt insect membranes without harming plants.

What do scale insect eggs look like?

Eggs appear as tiny ovals under female scales, often yellow or purple. They hatch into pale crawlers within 1-3 weeks. Use magnification to spot them beneath dome-shaped covers before they disperse.

Should I scrape scales off my plants?

Gently scrape heavy infestations with a toothbrush dipped in soapy water. This removes adults but won't eliminate eggs. Follow with oil sprays to target hidden crawlers. Avoid harsh scraping that damages plant bark.

Do scale insects crawl or jump?

Only crawlers (young nymphs) move using legs. Adults cement themselves to plants, losing all mobility. Scales cannot jump; crawlers crawl slowly or drift on wind currents to new hosts.

How long do scale insects live?

Females survive 2-6 months, laying eggs continuously. Males live days after mating. Life cycles vary by species: some complete generations in weeks, while overwintering scales persist for months.